Bode, Katherine, Australian National University, Australia, katherine.bode@anu.edu.au

Overview

Drawing on the AustLit: the Australian Literature Resource database,1 this paper uses quantitative and computational methods to offer new insights into literary history: in this case, gender trends in the contemporary Australian novel field.

AustLit

AustLit is currently the most comprehensive and extensive online bibliography of a national literature. Created in 2001, AustLit merged a number of existing specialist databases and bibliographies, and has subsequently involved well over a hundred individual researchers – from multiple Australian universities and the National Library of Australia – in an effort ‘to correct unevenness and gaps in bibliographical coverage’ and continually update the collection. The database has received significant government and institutional funding and support, and includes bibliographical details on over 700,000 works of Australian literature and secondary works on that literature. In addition to its high degree of comprehensiveness, AustLit is well suited to quantitative and computational analysis due to its construction according to established bibliographical standards and fields, which gives the data a high degree of consistency across the collection. This study focuses on Australian novels, the most comprehensively recorded aspect of AustLit. Even so, AustLit notes that its ‘coverage of some popular fiction genres such as westerns and romances, and of self-published works, is representative rather than full’.2

Methodology

Although AustLit is generally used by researches for individual queries, it also has a guided search function that allows a large number of results to be extracted as tagged text. Using this function I constructed searches that returned information, including the author, date and place of publication and genre, for all Australian novels published between 1945 and 2009. I then used Apple OS X command lines to organize the data before exporting it to CSV format. Once in this format, I searched all the author names in AustLit to discover any pseudonyms and to determine if the authors were male or female. I explored the data in Excel, using the pivot table function to query the data and the chart function to visualize of trends over time.

My approach to this data is based on a combination of book history’s awareness of the contingency and limitations of data, and the paradigm of computer modeling as outlined by Willard McCarty in Humanities Computing.3 Although there has been virtually no conversation between the two fields, the methodological underpinnings of book history and the digital humanities together signal important directions for developing a critical and theoretically aware approach to working with data in the humanities. Quantitative book historians explicitly acknowledge the limited and mediated nature of data, and provide clear and detailed accounts of the origins, biases and limitations of the literary historical data they employ. In presenting their results, such scholars insist that quantitative results provide a particular perspective, suited to the investigation of some aspects of the literary field but not others, and offer indications rather than proof of literary trends. As Robert Darnton writes, ‘In struggling with [literary data], the historian works like a diagnostician who searches for patterns in symptoms rather than a physicist who turns hard data into firm conclusions’.4

Although developed for use with language, McCarty notion of modeling – as an exploratory and experimental practice, aimed not at producing final and definitive answers but at enabling a process of investigation and speculation – can be adapted for analysis and visualization of literary historical data, and employed in ways that resonate productively with quantitative book historical methods. Specifically, I used a modeling approach to explore a series of hypotheses about trends in Australian literary history. For instance, the gender trends in authorship in a given period might lead me to suppose a particular hypothesis (such as the influence of second-wave feminism on constructions of authorship). In enabling modification of or experimentation with data – for instance, subtracting particular publishers or genres – modeling provides a way of testing such ideas, with the results of different models either fulfilling and strengthening, or challenging, the original hypothesis. This methodological framework shows how relatively simple computational processes in Excel can enable a process of thinking with the computer that reveals trends, conjunctions and connections that could not otherwise be perceived.

This combination of book historical and digital humanities methods avoids what I see as limitations in other ‘distant readings’ of the literary field, including Franco Moretti’s well-known ‘experiment’ in literary history: Graphs, Maps, Trees.5 In particular, the skeptical approach to data encouraged by book history avoids the portrayal of quantitative results as objective and transparent. Meanwhile, McCarty’s notion of modeling – as a means of thinking with the computer – avoids the assumption that the computer is a passive tool in the process of analysis and interpretation.

Results

Extracting data from this online archive, visualizing and modeling it, has allowed me to address questions of long-standing interest to literary scholars and to explore new and hitherto unrecognized trends in Australian literary history. This paper illustrates the potential of such research for literary studies with a case study that responds to the conference theme of ‘digital diversity’. A major issue in literary historical discussions of ‘diversity’ is the presence – or absence – of women authors in the literary field. In contemporary literary studies (in Australia and other national contexts), such discussion has focused on the period from the late 1960s to the late 1980s, when second-wave feminism is said to have had its major impact. This period is cited as a time of substantial growth in women’s presence in the literary field, leading to increased diversity and a deconstruction of the canon of male authors. Visualisations of the AustLit data allows me to explore whether this perception of gender trends is warranted, while the process of modeling enables investigation of the causes of the trend.

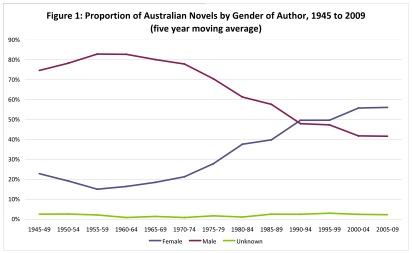

In relation to gender trends from the late 1960s to the late 1980s, the results of this study support the longstanding perception that women’s involvement in the Australian novel field increased at this time (see Figure 1, showing the proportion of Australian novels by men and women from 1945 to 2009). However, the outcomes of the modeling process significantly complicate the standard interpretation of this trend, and the relationship between politics and the literary field it implies. Contextualising this growth in women’s writing in relation to the genre of Australian novels shows that the largest area of growth was in romance fiction, a form of writing usually seen as inimical to second-wave feminism.

Another challenge to existing interpretations of the relationship between gender, politics and fiction emerges in the past two decades, when gender trends in authorship are explored in the context of gender trends in critical reception. In the 1970s and 1980s, even as romance fiction represented the largest proportion of women’s publishing, critical attention to Australian women writers in newspapers and academic journals increased (see Figure 2, depicting the proportion of men and women among the top twenty most discussed Australian novelists in these different forums and overall). The proportion of Australian novels by women has continued to grow in the past two decades, such that they write well over half of all Australian novels published in the 2000s (see Figure 1), and the proportion of romance fiction in this field has declined. Yet in this same period, women writers have been less and less the subject of critical discussion in newspapers. These results resonate with those recently presented by Vida, an advocacy group for women writers, showing the same prevailing focus on male authors in the book reviews of a wide range of major American and European newspapers and magazines in 2010 and 2011, including The Atlantic, the London Review of Books, the New York Review of Books and the Times Literary Supplement.6

Although women continue to be well represented in academic discussion of Australian literature, the focus in that forum is on nineteenth-century authors, whereas both contemporary and historical male authors are discussed. Despite the impact of feminism on the Australian literary field, these results suggest that the longstanding perception of the great author as a man is still influential. Presence or representation is not, I argue, the only issue in determining the success of diversity in the literary field. Other constructions – relating to the genre in which fiction is written and gender trends in its reception – shape the field in ways that only come into view on the level of trends: when the literary field is approached as a system, using data-rich and computer-enabled methods.

Notes

1.AustLit. (2001-). AustLit. http://www.austlit.edu.au/ (accessed 25 March 2012).

2.AustLit. (2001-). About Scope. http://www.austlit.edu.au/about/scope (accessed 25 March 2012).

3.McCarty, W. (2005). Humanities Computing. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

4.Darnton, R. (1996). The Forbidden Best-Sellers of Pre-Revolutionary France. New York: Norton, p. 169.

5.Moretti, F. (2005). Graphs, Maps, Trees: Abstract Models for a Literary History. London: Verso.

6.Vida: Women in Literary Arts (2010). The Count 2010. http://vidaweb.org/the-count-2010 (accessed 19 June 2011); Vida: Women in Literary Arts (2011). The Count 2010. (accessed 9 March 2012).